Appendix 4 – The ETS should be coupled with other policies, but bespoke associated or unrelated policies are required that do not undermine the primary tool.

Intro

Improving efficiency and reducing consumption opens the door for a second elephant to enter the room – i.e. should the ETS be left alone or should it be coupled with other policies? It is the latter.

The CCC…

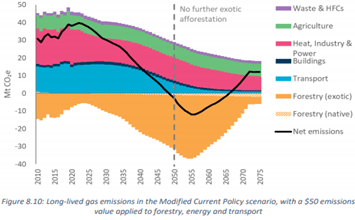

- Says that “net long-lived gas emissions are projected to fall from 36.3 Mt CO2e in 2018 to 6.3 Mt CO2e by 2050 under current policy settings.”[1]

- Says that “net zero emissions [can] be reached [by varying] … the current policy reference case assuming a slightly higher NZ ETS unit price of $50 … [by way of] new forest planting [which] increases to around 1.3 million hectares by 2050.”[2]

Discussion

- The ETS is a good mechanism and should (in theory) reduce emissions with a sinking lid.[3] So the debate shouldn’t be whether to replace the ETS, e.g. with a carbon tax[4] – but about whether other policies should be coupled with the ETS or if it should be left alone to work.

- The main benefit of an ETS is that it encourages least-cost abatement.[5] The efficient economics argument and evidence for leaving the ETS alone is therefore strong, e.g.:[6]

- “Once an ETS is in place, other abatement policies generally change the mix, not the quantity, of emissions reduction.”

- “Retaining existing, or introducing new, policies to supplement the ETS would need to offer other benefits … [e.g.] exploiting abatement potential in sectors and activities not covered by the ETS.”

- “All supplementary policies must be subject to rigorous evidence-based analysis to determine if their rationales are sound.”

- “[Design should] avoid [policy] overlap as a matter of principle as it inhibits the market effectiveness of … [an] ETS.”[7]

- An example[8] is Company A and B both pollute 100 t of emissions. An ETS caps emissions at 160 t in total. Both companies receive permits to pollute 80 t. It costs $1/t for Company A to reduce emissions and $10/t for Company B. They do a deal – Company A pays Company B say $5/t for its permits. Company A pollutes 60 t, and Company B pollutes 100 t, at the cap. An alternative is a $50/t subsidy paid to Company B to reduce emissions which fall to 60 t. Company A doesn’t reduce emissions as it doesn’t need to and the subsidy is wasted money that did not reduce emissions further vs. how emissions would have reduced anyway under the ETS.

- While that evidence is robust, supports the need for the ETS to be the primary tool, and says to avoid subsidies in areas directly covered by the ETS, the evidence actually proves the need for further policies in addition to the ETS. Reasons include:

- The same source as a quote above says “policies other than the … ETS will be needed in order to achieve cost-effective … emission reductions.”[9]

- A comprehensive scientific critique further agrees that other policies are needed.[10]

- The ETS excludes agriculture, shipping, aviation and trade.

- The ETS excludes a raft of policies and tools that are aimed at benefits other than directly reducing emissions, e.g. education, science, and waste practices for example – in line with most of the recommendations in this submission.

- The higher GDP and incomes go and the more efficient economies are, the more emissions are produced or imported as consumption.

- In the very long term presupposing a floor on the sinking cap due to having forestry offsets, as the price of carbon increases, the more polluters will abate, which will put downward pressure on the price of carbon, increasing the likelihood that those who had yet to abate would keep paying to pollute rather than reducing gross emissions.

- However, there is also a producer paradox (derived from e. and f. above) which supports the coupling of ETS with other policies. I.e. The ETS will struggle to reduce emissions that are tied to hard-to-abate consumer areas. E.g. the CCC says that petrol will increase 30c/l by 2035 as a result of its proposed emissions budgets[11] (let’s infer at $140/NZU). Yet few would be incentivised to switch to EVs for +30c/l. Even a carbon price of $1,400/NZU would only add +$3/l and may not move everybody to EVs. This supports the idea of a consumption tax – think of that as a way to apply higher ETS prices in a targeted way in hard-to-abate areas.

- Yet there is also another hidden producer paradox insofar as the ETS may perversely reduce emissions as the price of carbon increases by offshoring that production to developing countries that have less stringent and time-bound international targets (reducing New Zealand’s emissions, but increasing global emissions).[12] And if that happens to goods we need in New Zealand anyway (like food), that would increase net global emissions from production and transport, and negatively affect GDP, jobs and wellbeing. E.g.:

- Company A and B both pollute 100 t of emissions. An ETS caps emissions at 160 t in total. Both companies receive permits to pollute 80 t. It costs $0.05/t for Company A to move production offshore which increases pollution to 150 t.[13] Company A would hoard units or sell them to Company B. Company B would not reduce pollution. Domestic emissions would be 100 t, and global emissions would be 250 t.

- It also raises a question about whether New Zealand should rely on an associated policy of cheap overseas units to achieve its emissions reductions targets tomorrow, for example.[14] The answer is no. Using cheap overseas units:

- Is expressly against the Paris Agreement,[15] even though (paradoxically) it is permitted.

- Is against the requirement in the Act to aim for domestic reductions.[16]

- Would likely deprive a developing country of the difference between the full value of emissions sequestered and the cost to do so.

- Would likely deprive a developing country of its own net emissions sink and limit its emissions ability to grow its GDP and therefore quality of life and wellbeing outcomes.

- Would deprive New Zealand from the co-benefits associated with domestic reductions.

- Is not sustainable forever as other countries pursue their own net zero carbon goals.

- Okay, but if we circle back to the CCC’s conclusion that the NZU price can be $50/unit and New Zealand will achieve net zero carbon in 2050,[17] that raises the question about whether anything in the CCC’s report is even relevant. I.e. if we’re going to get there already (by planting more exotic forests),[18] should we do anything else? Yes, we should. Because:

- While that is a valid train of thought, it doesn’t rule out other policies that are coupled with the ETS that don’t cost much money and don’t target the same abatement areas.

- It is debatable whether foresters would plant more forests at $50/unit when the price of carbon in 2021 is already just 20% below $50/unit and emissions are not reducing.[19]

- The net zero carbon target is not actually a 2050 target, but it requires[20] “[net emissions to be] zero by … 2050 and for each subsequent calendar year.”

- The CCC models that a $50/unit price will not achieve net zero carbon on/from 2067:[21]

- It is for that reason that the CCC likely says that “marginal abatement costs of around $140 per tonne of CO2e abated in 2030 and $250 in 2050 in real prices are likely to be needed [in Aotearoa to meet the emissions budgets and ongoing 2050 target].”[22]

Conclusions

- The cap-and-trade ETS should remain as New Zealand’s primary emissions reduction tool.

- The ETS should be coupled with associated policies that tweak it so as to mitigate against perverse outcomes related to carbon leakage and use of offshore units. Failure to manage this properly will likely result in New Zealand using carbon accounting tricks at some stage in the future and/or will undermine New Zealand’s climate change leadership.

- The ETS should be coupled with other policies that directly target other areas that are not covered by the ETS (e.g. consumption, shipping, aviation, and trade).

- The ETS should be coupled with other policies that don’t cost much money (e.g. education, networks, and others suggested in this submission).

- The waterbed effect is real, but it doesn’t undermine the conclusions above. The main learning is that the CCC should not pursue policies that apply money to abate the same areas that the ETS seeks to abate as that will waste money and won’t reduce emissions.

- The CCC is incorrect to imply that it can fix the waterbed effect across periods,[23] as doing so would only change the trajectory of the forward sinking lid and wouldn’t remedy abatement actions that weren’t happening at least cost. If an attempt to correct for the waterbed in future periods was done, that would accelerate economic destruction, undermine the CCC’s advice, undermine emissions budgets once set, and interfere in the market too much. Future emissions budgets should operate on a ‘no-material-surprises’ basis.

Recommendations

- Recommend that agriculture, shipping, aviation and trade are brought into the ETS as soon as possible.

- Recommend keeping the ETS but reviewing it independently from a scientific and first principles perspective.[24] E.g. consider dropping food producers from the ETS (or guaranteeing 100% free units) for food produced for domestic consumption if and to the extent that that production would be forced offshore only for the food to be imported again.

- Analyse each recommendation in the draft report to ensure that those do not directly target areas that are already covered by the ETS with things like subsidies.[25]

- Better talk through the concepts from this appendix in the draft report and associated chapters of evidence.

- Recommend that any offshore use of units doesn’t harm developing countries.

[1] Page 46 of the draft report.

[2] Page 46 of the draft report.

[3] https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/explainers/how-do-emissions-trading-systems-work/

[4] That is a red herring – both are similar and should achieve similar outcomes.

[5] https://icapcarbonaction.com/en/?option=com_attach&task=download&id=575 at page 13.

[6] https://www.pc.gov.au/research/supporting/garnaut-emission-trading/garnaut.pdf at page 12, for the first three points.

[7] https://www.ieta.org/resources/EU/IETA_overlapping_policies_with_the_EU_ETA.pdf at page 1.

[8] Inspired from https://oliverhartwich.com/2020/12/10/effective-and-affordable-why-the-ets-is-sufficient-to-deal-with-the-climate-emergency/

[9] https://www.ieta.org/resources/EU/IETA_overlapping_policies_with_the_EU_ETA.pdf at page 2.

[10] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272786779_Ten_reasons_why_carbon_markets_will_not_bring_about_radical_emissions_reduction

[11] Page 84 of the draft report.

[12] www.nature.com/articles/s41599-019-0298-6

[13] As that developing country likely has more thermal generation than New Zealand.

[14] Something that arguably the CCC has not wholly considered.

[15] Paragraph 2 of Article 4.

[16] r5Z

[17] Page 46 of the draft report.

[18] Page 17 of https://ccc-production-media.s3.ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/public/evidence/advice-report-DRAFT-1ST-FEB/Evidence-CH-08-what-our-future-could-look-like-28-Jan-2021-compressed.pdf

[19] https://www.stats.govt.nz/tereo/indicators/new-zealands-greenhouse-gas-emissions albeit that the latest data is from 2018, and even in 2020 the cap had yet to come into force. Nevertheless, anecdotally there are schools of thought that emissions continue to remain flat or are not decreasing in 2021, e.g.: https://www.newsroom.co.nz/nz-emissions-to-rise-through-2022.

[20] r5Q of the Act.

[21] Page 17 of https://ccc-production-media.s3.ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/public/evidence/advice-report-DRAFT-1ST-FEB/Evidence-CH-08-what-our-future-could-look-like-28-Jan-2021-compressed.pdf

[22] Page 129 of the draft report.

[23] Page 10 of https://ccc-production-media.s3.ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/public/evidence/advice-report-DRAFT-1ST-FEB/Evidence-CH-16-Our-approach-to-policy-20-Jan-2021.pdf

[24] The second bullet point on page 132 of the draft report is sub-standard.

[25] The last paragraph in the box on page 10 of https://ccc-production-media.s3.ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/public/evidence/advice-report-DRAFT-1ST-FEB/Evidence-CH-16-Our-approach-to-policy-20-Jan-2021.pdf is correct, but the CCC doesn’t appear to have done this justice in the draft report.